Cigarette sales are collapsing as Americans continue to quit smoking. Yet tobacco profits continue to rise.

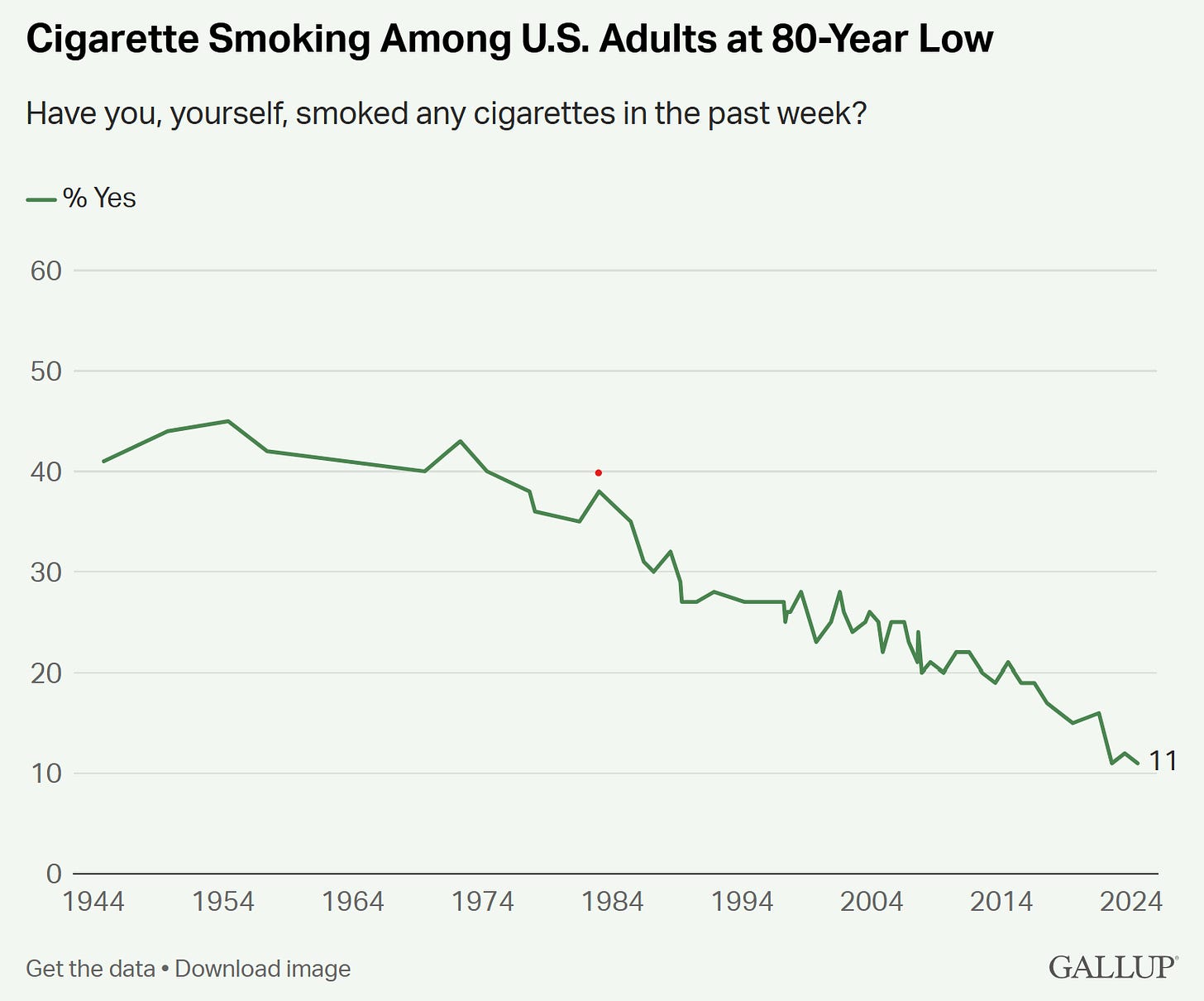

One of the greatest public-health victories in the United States has been the dramatic decline in cigarette smoking. In 1954, 45% of Americans told Gallup they had smoked a cigarette in the past week. Today, that share is just 11%, a drop of -34 percentage points.

The decline in smoking has translated into a collapse in cigarette sales. Between 2015 and 2021 alone, annual sales of cigarette packs fell from 12.5B to 9.1B. That’s a whopping -27% decline. Yet in recent years, US tobacco companies have been on a surprising hot streak.

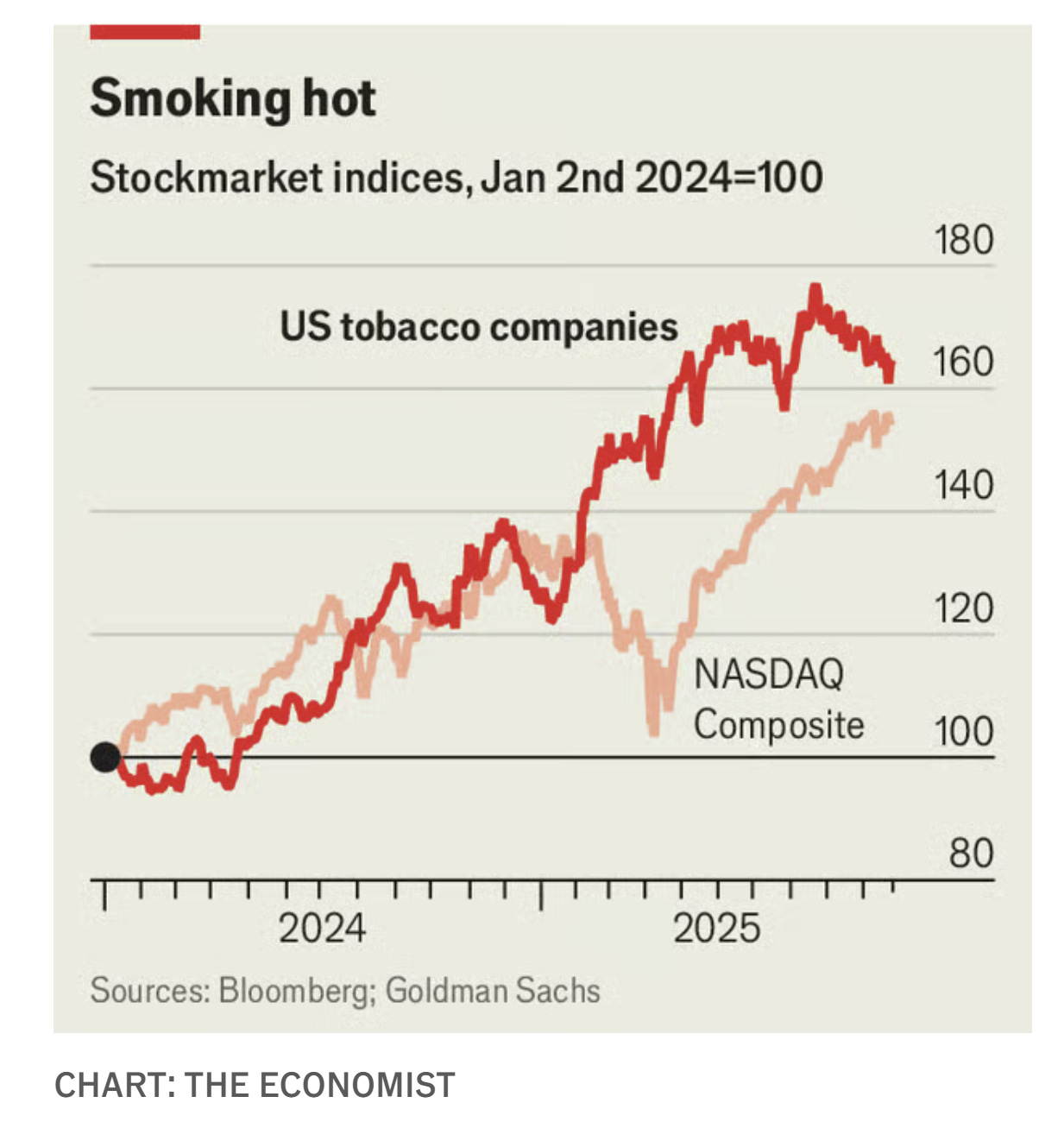

Since January 2024, $100 in the white-hot Nasdaq would have grown to $160, but US tobacco stocks would be sitting closer to $165. In the last few years, the operating margins on cigarettes in America have climbed by +10 percentage points to 60%. And the industry is expected to generate $22B in operating profits by year’s end.

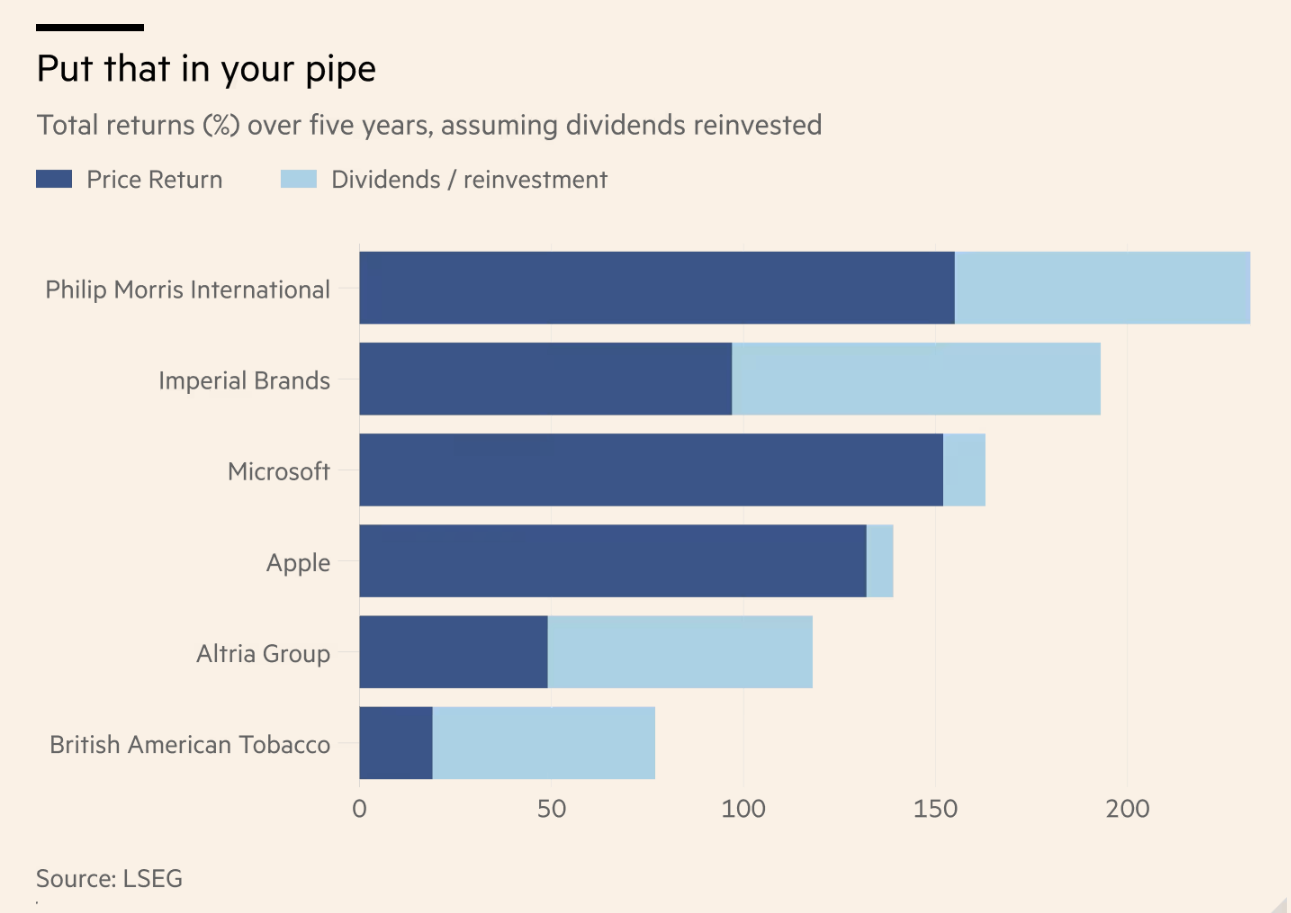

Over the past five years, some cigarette stocks have even outperformed Microsoft and Apple, according to an analysis by the Financial Times.

Why are tobacco companies thriving even as smoking rates plummet? Price elasticity. When cigarette smoking was widespread, many consumers were quick to cut back when prices rose. But as the habit has waned, the remaining smokers tend to be the most committed (read: most addicted) and therefore the least price-sensitive. These price-inelastic consumers keep buying even as costs climb. As a result, cigarette prices have been rising much faster than inflation: In 2024, while overall consumer-price inflation grew by 3%, the price of Marlboros jumped by more than 7%.

In a free market, Adam Smith teaches us, competition should drive prices down to near the cost of production. But there’s nothing competitive about the US cigarette business: It’s effectively a duopoly dominated by Altria and British American Tobacco. Vast and complex layers of government regulation deter smaller rivals, preserving the incumbents’ market power and confirming the old dictum that heavy regulation tends to help big firms build deep moats. And with only two major players, it’s far easier for the big guys to keep prices high and profits higher.

Some things:

1) We're seeing more people who do smoke smoke as an occasional vice rather than a daily habit. Depending on the nature of the survey, they may or may not be classified as a smoker (i.e., they might not have smoked in the last week). But in any case, they are less likely to be price-sensitive because of their rather low consumption--comparing someone who smokes one pack a month vs one or more packs a day.

2) Related to 1), I would expect this to drive sales of full-priced brands over discount brands, leading to higher per-pack margins. If you're only smoking occasionally, you're not looking for a cheap fix.

3) Also related to 1), it seems nowadays that only the heaviest smokers still buy cigarettes by the carton. Many moderate smokers who feel ambivalent about their habit will pay extra buying one pack at a time to avoid "committing" to 200 cigarettes at a time, even if it would make significant economic sense to buy cigarettes by the carton. A light smoker won't consider buying a carton. Of course, this drives up per-pack margins as well.

4) With most forms of advertising banned for all manufacturers, this significantly lowers marketing costs and also increases margins. It also creates massive barriers to entry. The limitations on "light/low-tar" cigarettes also eliminates a significant R&D expense; there's no incentive for making a seemingly (and spuriously) "healthier" traditional combustible cigarette.

5) It seems like cigarette sales are clustering around just a handful of brands and styles, most notably Marlboro Gold (Lights) as the canonical example. Not having to support so many low-selling brands has to be a cost savings as well.

As an aside, I have often wondered why so many smokers smoke Marlboros, especially as advertising has been curtailed and banned over the years. Lock-in? Following the crowd? Is there something particularly appealing about Marlboro from a functional POV? Or have they simply become the "Coca-Cola" of cigarettes, that is, a ubiquitous brand available everywhere?

As I've said before: those who drink, drink. Same applies to smoking: those who smoke, smoke.