According to a new poll, Gen Xers are the least likely to agree that becoming wealthy is an achievable goal. Only 47% of 45- to 54-year-olds agree with this statement, compared to 60% of 18- to 34-year-olds and 57% of seniors age 65+.

In Say Anything…, the 1989 teen classic, the valedictorian played by Ione Skye Lee announces, “Having taken a few courses at the university this year, I’ve glimpsed the future, and all I can say is… go back!”

According to a new survey of Americans aged 18 and over, many Gen Xers may now be wondering if they should have taken her advice. The survey, commissioned by Fast Company and carried out by Harris (cross-tabbed data available here), shows Xers to be uniquely challenged economically and uniquely pessimistic about their future. It also offers revealing insights into other generations.

Harris uses popular generational definitions: Gen Z born in or after 1997; Millennials born in 1981-96; Xers born in 1965-80; Boomers born in 1946-64; and Silent born in 1928-45. (I don’t use these definitions; but Harris helpfully provides age breakdowns so we can understand better which birthyears really matter.)

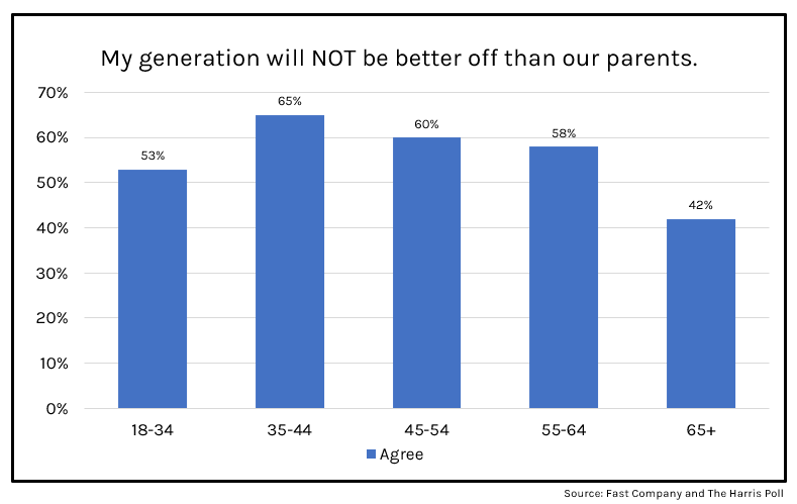

Let’s start with that familiar indicator of generational optimism. Agree or disagree: My generation will not be better off than our parents?

The dismaying reality is that most Americans today agree: 54% of the Harris respondents say they will not be better off. This is true btw not just in America, but in most other high-income countries. (See “Post-Pandemic Pessimism.”)

If you take out the 65+ group (only 42% of whom agree), the average for non-senior adults rises to just over 60%. And if you further take out those relatively optimistic Millennials under age 35 (only 53% of whom agree), the share rises to 62%. That leaves the three heavily Xer age brackets: 35-44, 45-54, and 55-65, where the shares agreeing are 65%, 60%, and 58%, respectively. The pessimism maxes out with late-wave Xers and some Xennials born in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

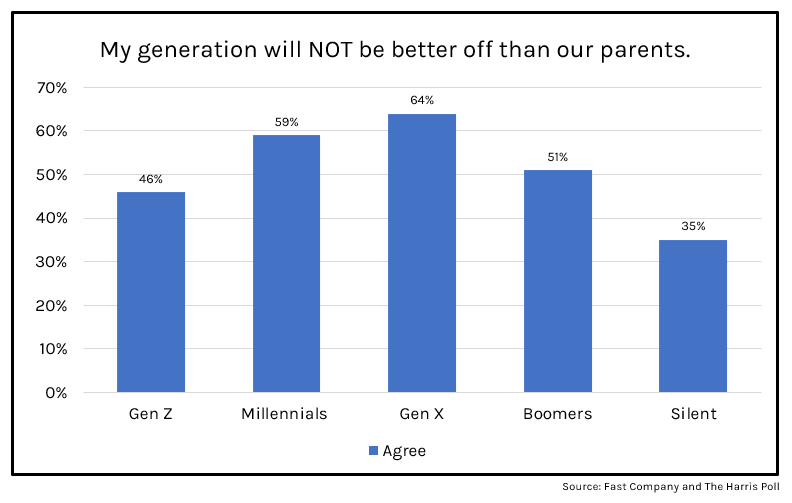

Using age brackets alongside Harris’s generations, here’s how it plays out.

The big U-shaped pattern reflects two dynamics.

First, among all Americans today between age 60 and 80, there’s a steep slowdown by birthyear in upward economic mobility. For those born before the early 1940s (that is, for the Silent), the overwhelming majority enjoyed gains in real income over their parents at the same age (30 or 40). Thereafter, the Boomer birthyears represent a steady decline in this share, with late-wave Boomers enjoying only a bit better than even odds of outearning their parents. See this classic chart by Harvard’s Raj Chetty.

Mobility continues to fade gradually by birth cohort for Xers and Millennials. But among later-wave Millennials, a new dynamic takes over: optimism. Millennials now hitting age 30 may feel they have a lot of time left to catch up to their parents even if they haven’t yet done so. And many “Gen Zers” may be too young to have any idea how their income potential measures up against their parents’.

Now let’s look at another core indicator of optimism. Agree or disagree: In the United States, becoming a member of the wealthy/elite class is an achievable goal?

Again, Gen X stands out. It is the only generation to disagree, albeit by a thin margin, 49%-51%. Boomers are almost as pessimistic, at 52%-48%. The Silent and Millennials, on the other hand, come out clearly on the Horatio Alger side of this question. (Gen Zers fall off here, probably because many may not consider “wealthy/elite” to be a socially desirable goal—as opposed to, say, merely affluent or secure.)

Let’s move on to perceptions of class: At what income level would you classify your household? Respondents can choose among three broad categories, each divided into two. There’s upper class (elite/wealthy and affluent); middle class (upper-middle and lower-middle); and lower class (working class and low-income). Here are the responses by broad category.

Gen X has the largest share who self-identify as “lower class”: 43%, versus 35% for all other generations. These Xers divide about equally into lower income (20%) and working class (23%), each also the highest of any generation. Xers have the smallest share in the “upper class” (only 2%). And they are tied with Zers for the smallest middle class (54%).

The middle class would have been larger for Gen Z had not such a large share of Zers—8%, the largest of any generation—deemed their household to be in the upper class. Most Zers in fact live with their parents, and many may have no realistic idea what their household income is.

Boomers have the smallest “lower class.” They are about as likely as Xers or Silent to identify as working class—but apparently few Boomers will admit to being merely “lower income.” Only 9% described themselves this way, versus 20% of Xers and 15% of Silent.

Harris gives us guidance on how each generation interprets class. It asks respondents to estimate the upper and lower income boundaries of “middle class.” The values shown here are the median responses.

Boomers and Xers have the broadest definition of middle class in terms of income ($50K to $100K). This makes it even more striking that such a small share of Xers believe they belong to it.

Xers also place its lower boundary higher than younger generations do, which may explain their larger low-income share. But their higher low-income line is probably justified. After all, Xers live in larger households with more dependent children than younger households. Xers at age 50 also have to handle college tuition, family health insurance, and residence in a decent school district—burdens not confronting as many Millennials at age 30.

Let’s move on to perceptions of inequality. Agree or disagree: There is a growing income gap in the United States?

Overall, 84% of Americans agree. 36% agree strongly; only 5% disagree strongly. Although all generations widely agree on this question, older generations agree the most—undoubtedly because they recall best an America in which the rich-poor gap was smaller.

Respondents were then asked whether the size of America’s middle class, in numbers of households, had increased or decreased over the past decade. And what would happen to it over the next decade. On average, a small majority said increase over decrease in both decades. But over the next decade, more said “decrease a lot” than “increase a lot.” Xers and Boomers were the most pessimistic in their outlook.

Harris threw in two policy questions.

By 65% to 35%, respondents are negative on the wealth limit. Only Gen Z break even at 50-50%. Older generations disagree by progressively larger margins, with the biggest jump separating Xers from Millennials. By 70% to 30%, respondents agree on the anti-savings effect of current tax policies, including most Gen Zers.

Harris’s crosstabs offers some further perspectives worth mentioning.

By gender, women were markedly more pessimistic than men across nearly all questions. Women of all ages were only 50-50% split on whether joining the wealthy/elite is achievable. They believed the middle class shrank over the last decade. And they agreed they will not do better than their parents’ generation by 58-42%, while men were nearly evenly split on this question.

Gen-X women really stand out on their negative assessment of generational progress. Fully 74% of women age 35-44 said their generation will be worse off than their parents’. An impressive 67% of women age 45-54 said the same. Older women age 65+ were much more positive: Only 42% said their generation will be worse off. This disparity deserves a whole new survey—if not an in-depth focus group.

By region, the Northeast and West are the most optimistic and the Midwest is the most pessimistic. By 45-28%, Midwesterners believe the middle class shrank over the last decade. And by 40-29%, they believe it will keep shrinking over the next. By 58-42%, they believe they will not do better than their parents’ generation. In the Midwest, only 1% of respondents defined themselves as upper class (“affluent” or “wealthy/elite”) versus 3% in every other region.

The South, remarkably, has the lowest regional definition of what defines middle class ($45K to $75K) yet also the largest self-defined “lower class” (39%) of any region. It also has the smallest “middle class.” This matches what we already know from Census data: The South has the lowest per-capita income and the highest inequality (gini coefficient) of any region.

Even so, the South remains more optimistic about the future than the Midwest—which is probably why Americans are immigrating to one and emigrating from the other. These migrants to the South are, disproportionately, young—Millennials and Xers .

Let’s end where we started, with the travails of Generation X. They didn’t expect things to turn out this way. Back as college freshmen in the late ’70s and ‘80, a large and rising share of them said “getting ahead financially” was very important to them—much more important than it had been for Boomer frosh.

Then something happened. To paraphrase from another Xer movie classic (True Colors), Xers may not have gotten what they wanted or needed—yet neither have they gotten what they deserved. And that’s the bottom line: Xers deserved better than what they’ve gotten thus far.