Remote work has outlasted the pandemic and reshaped how cities function. Its effects are now showing up in office markets, housing prices, and city budgets.

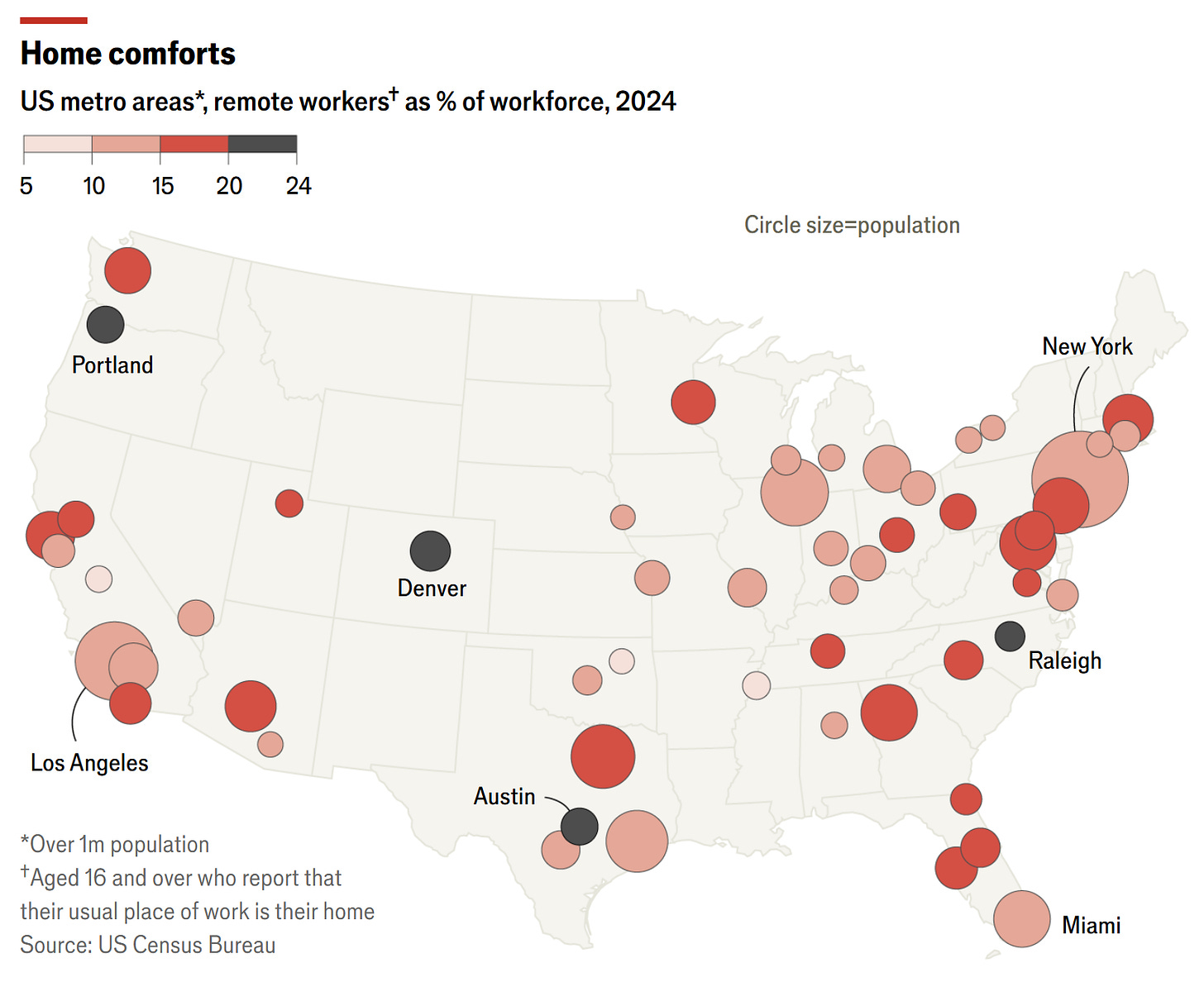

Since the pandemic, most white-collar workers have settled into hybrid schedules. (See “Remote Work Is Here to Stay—Especially If You Speak English.”) Yet a meaningful share of employees remain fully remote. Across metro areas with populations above one million, about 15% of workers now telecommute every day. That figure is even higher in cities like Portland (20%), Denver (21%), Raleigh (23%), and Austin (24%).

These workers still live near urban amenities, but are no longer commuting downtown. As that shift becomes entrenched, the economic impact on city centers is becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

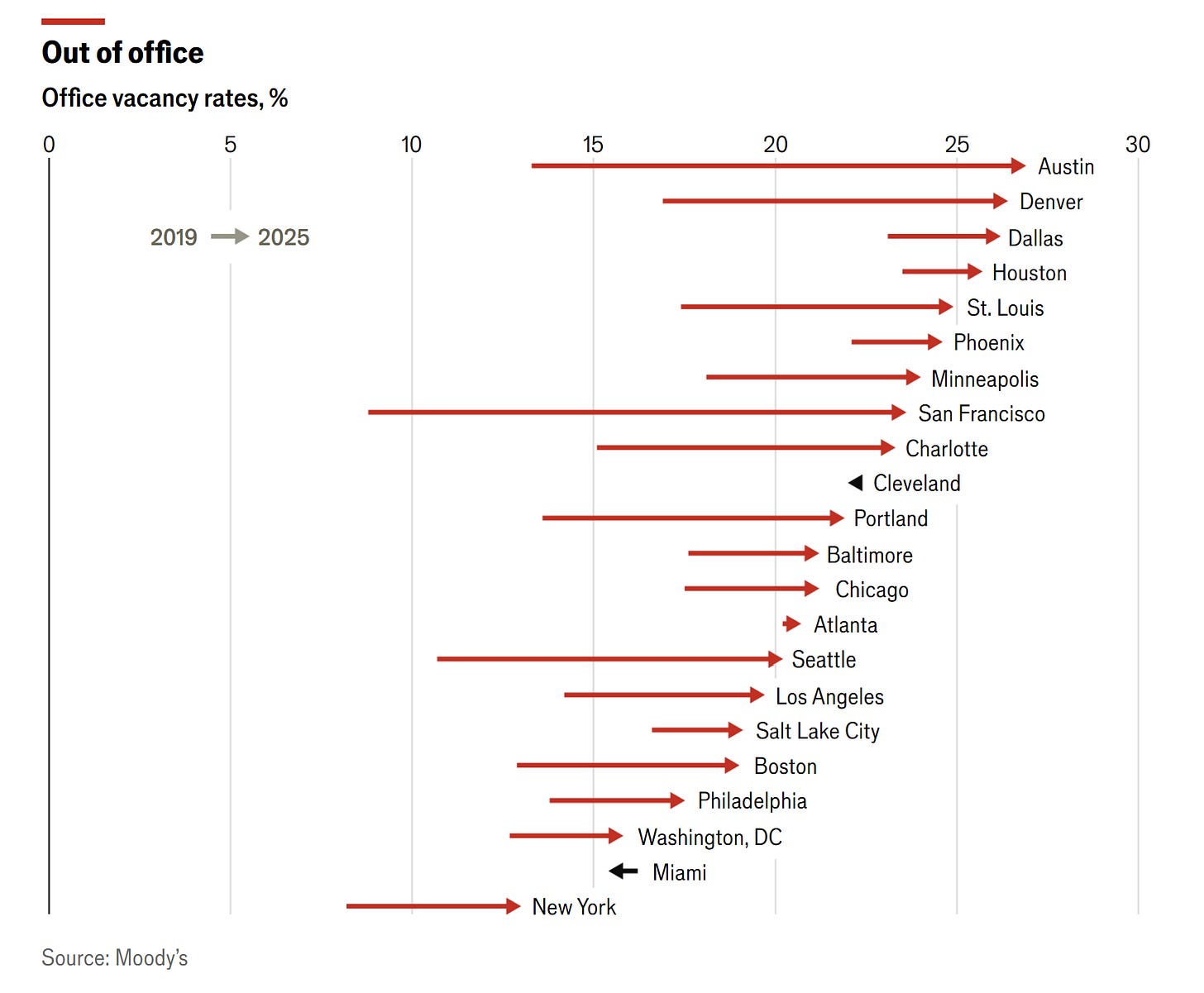

Most WFH cities are still grappling with elevated office vacancies. In Austin and Denver, more than 25% of office space now sits empty, the highest rate among major metros. In Austin, commercial and residential property values are projected to fall by -10% in 2026. At the same time, San Francisco’s post-pandemic collapse in office demand is expected to reduce property tax revenue by $150 to $200 million per year between 2023 and 2028.

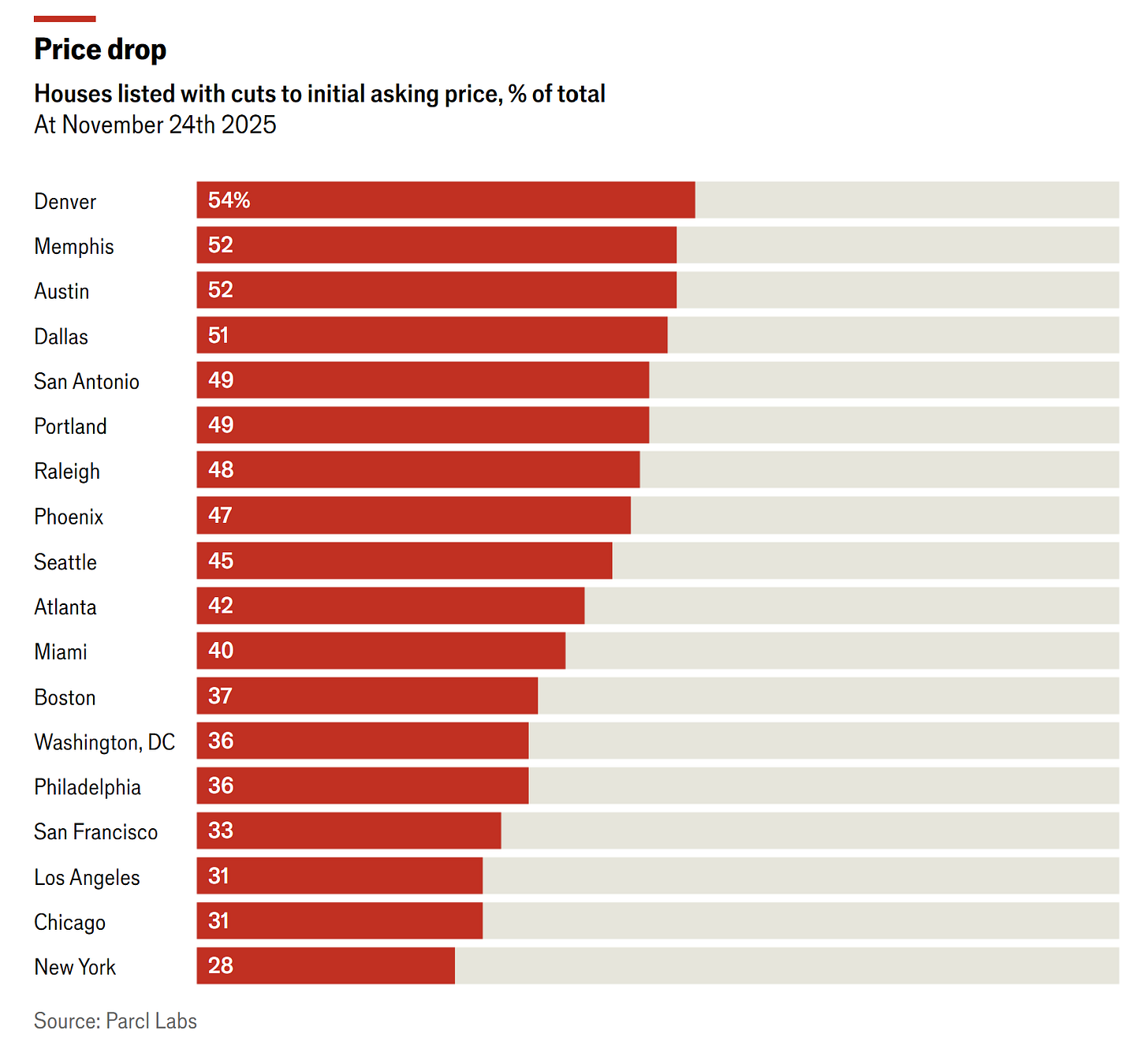

During the peak of the lockdowns, some of these WFH cities benefited from positive net migration, especially those in the Sunbelt and Midwest. But that trend has since slowed, and elevated interest rates have put downward pressure on housing prices. According to Parcl Labs, over 50% of homes for sale in Austin and Denver have cut their initial asking price.

Many WFH cities are also cutting public sector jobs to address mounting budget shortfalls. Last August, Denver initiated mass layoffs and eliminated a large number of vacant positions, together accounting for 7.6% of the city’s workforce. Austin has cut funding for emergency medical services and public parks. Meanwhile, San Francisco’s mayor has asked city departments to identify $400 million in spending cuts for 2026.

Remote work is no longer just a fight between workers and bosses. It is increasingly a public finance story, with city governments forced to shrink alongside their downtowns.

I wonder--this piece seems to blame the worker a bit. Can't adequate taxation on corporations "fix" this issue?