The Incredible Shrinking Family

Falling fertility will cause family support systems to shrink—and likely cause government to grow.

When was the last time you relied on your extended family for help? If you’re like most Americans, you have no problem recalling. Maybe one or two of your cousins helped watch your kids when they were small, or your grandfather gave you a loan to start your first business. Maybe Aunt Sara let you board at her place in your 20s, or Uncle Joe introduced you to your last employer. If you live in the United States, you’re more likely than not to live near them: In a 2022 Pew survey, more than half of Americans (55%) said that they live within an hour’s drive of at least some of their extended family members.

A recent YouGov survey corroborates Pew’s results by finding that 54% of Americans say that at least one member of their extended family lives “in their city or town” or closer. One in five (19%) say that this person lives in their own household.

Now imagine a world in which most of these extended family members are no longer around. Sounds dark—but this isn’t a mere thought experiment. One of the biggest trends that will accompany lower fertility rates is a shrinking of these family kinship connections.

What will future families look like?

In general, when we analyze falling birthrates, it’s through the lens of “vertical” (or “beanpole”) family members. Fewer births means fewer descendants like children and grandchildren. But it also means fewer “horizontal” family members, because smaller families and fewer siblings means fewer aunts, uncles, nieces, and nephews.

The evolution of family kinship networks is the focus of a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The researchers set out to create a model for kinship network projections comparable to long-term projections on population size and structure produced by organizations like the the U.N. and the World Bank. Using period data and projections for fertility and mortality rates, they produced kinship structures for every country in the world from 1950 to 2100.

The results are eye-opening. They identify three main trends in future kinship structure: (1) a sustained decline in family size; (2) a shift towards more “vertical” family networks, particularly in societies where fertility is declining most rapidly; and (3) a growing age spread among extended family members occupying the same generational tier (for example, among all cousins or among all uncles).

Drastic global shrinkage in total family size

Let’s examine these one by one. First, the shrinking size of extended families.

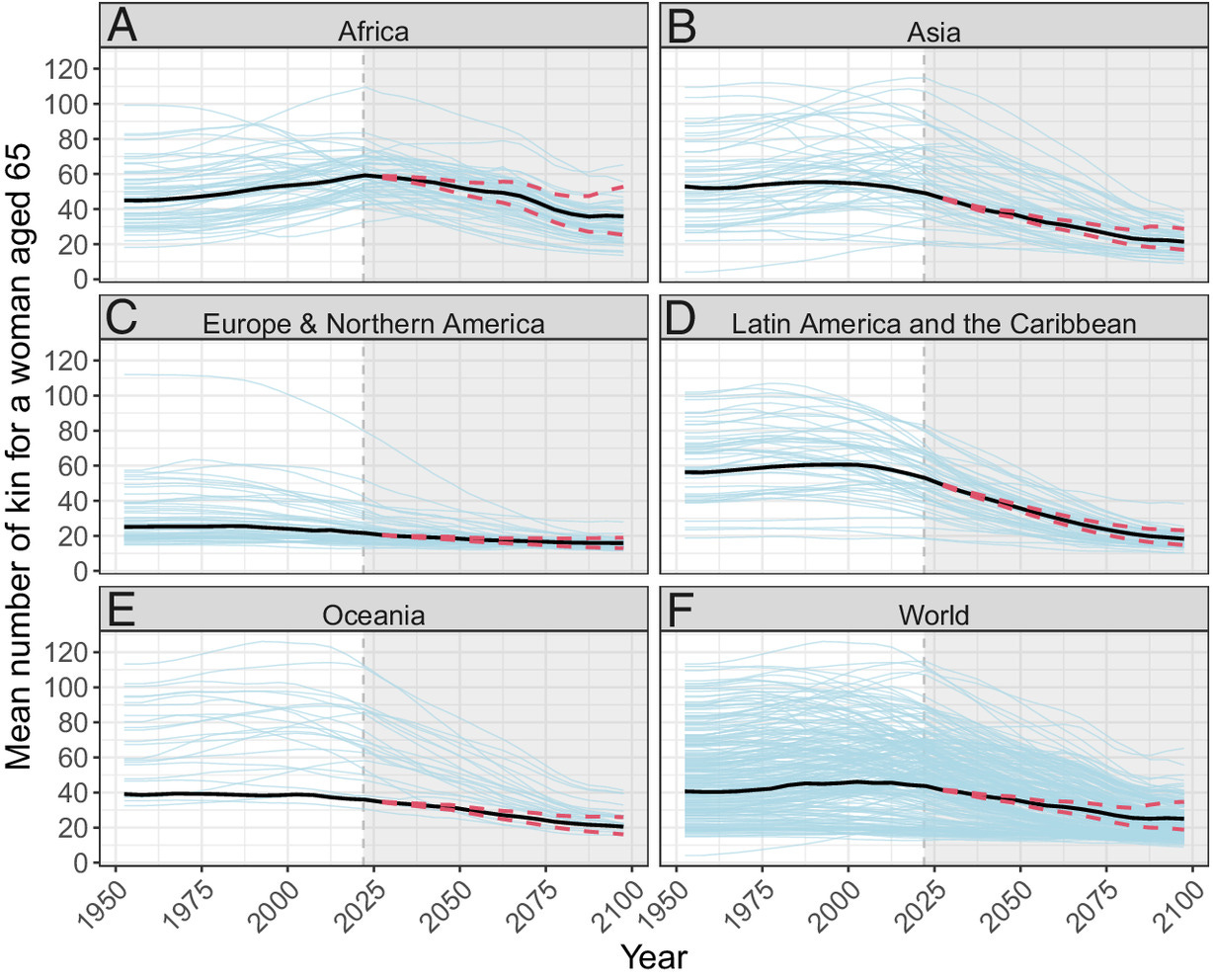

The next chart shows the total family size of a randomly selected woman in the population (dubbed “Focal” by the researchers) at age 65, by region, from 1950 to 2100. Here, “family size” counts all nuclear and extended family members: living great-grandparents, grandparents, parents, children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, siblings, and cousins. The blue lines show country-level values and the red dotted lines lower and upper 80% projection intervals for each region.

Notice that the magnitude of decline in total family size varies dramatically by region according to ongoing trends in fertility rates and how much they are expected to fall in the future. Since fertility rates are relatively low and families relatively small in North America and Europe (and have been so for quite a while), the change will be more moderate than in other regions. Even so, it’s quite significant. Family size in these regions is projected to decline from 25 living relatives in 1950 to 16 in 2095, or a -37% reduction.

The decline will be much steeper in Asia and steepest of all in Latin America and the Caribbean. Family size in Asia will shrink by roughly -60%, from around 50 relatives in 1950 to around 20. In Latin America and the Caribbean, it will go from 56 relatives to 18, or a -67% reduction.