This Election Will Be a Cliffhanger

Just when Harris appeared to be in the passing lane, the gaps are narrowing again. Trump's strategic advantages meanwhile begin to loom larger.

“I like the noise of democracy.” —James Buchanan

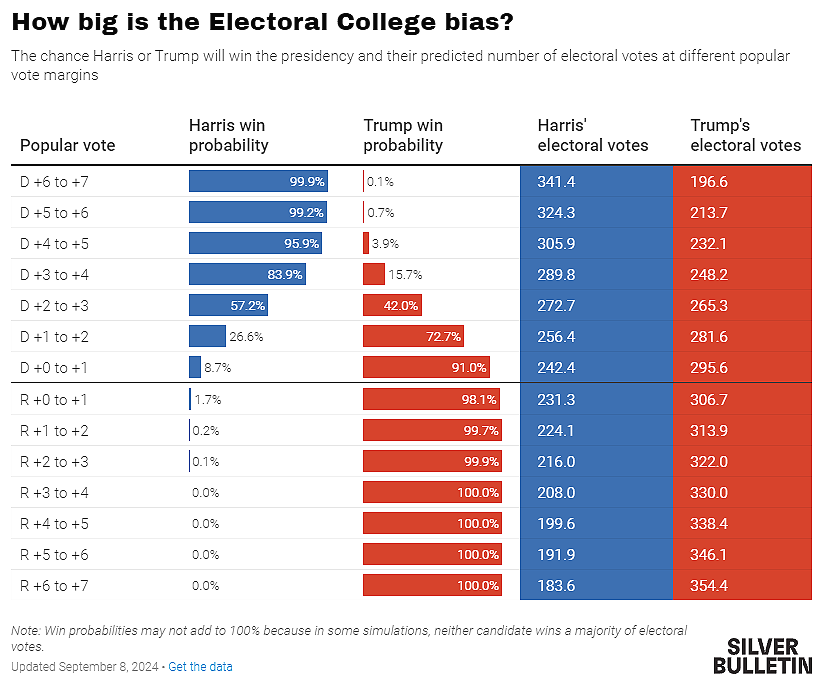

Now that we’re past Labor Day, get ready for a wild two-month home stretch in the 2024 presidential election race. So what can we expect? The betting markets currently rate the outcome as a coin flip. Polymarkets puts Trump ahead of Harris at 52% to 46%; PredictIt puts Harris ahead of Trump at 52% to 50%. (You can see all the bookmaker odds here.) Famed forecaster Nate Silver, who models the electoral college outcome by looking at state polls and figuring in structural modifiers like economic “drag” and convention “bounces,” last Friday boosted Trump’s odds significantly. He now puts him ahead of Harris at 63.8% to 36.0%—even though (44% to 56%) he expects him to lose in the popular vote. Because they’re so close, any of these odds could reverse at any moment.

Notice btw that the two numbers published by Silver don’t add up to 100.0%. That’s to allow for the 0.2% chance that the electoral college will tie. There are several such scenarios. Imagine, for example, that (among battleground states) Harris wins NV, AZ, and GA while Trump wins PA and MI. Poof! We’re tied at 269 to 269. That means the newly elected House of Representatives will vote by state for the winner on or shortly after January 6, 2025. Trump would be heavily favored to win such a vote, unless the Democrats enjoy a tidal victory in the House elections (which by assumption would be unlikely, since in that case Harris would have won in the electoral college).

This toss-up forecast may sound odd to any casual observer who has recently been watching the polls. After all, since the beginning of August, Harris has been in front of Trump in nearly every one of the hundred or so national polls tracked by 538 and sometimes ahead by large margins like 5%, 6%, or 7%. According to Silver, the recent moving average of national polls shows Harris ahead by +2.5%; according to 538, by +2.8%; and according to RCP, by +1.4%. And while the state polls are to be sure less accurate and less frequent, some of the recent battleground state results are enough to demoralize the most ardent Trump backer, like the +4% Harris lead over Trump in MI, PA, and WI reported a month ago by the NYT-Siena College poll (Aug 5-9). And then there’s momentum. Hands down, the Big Mo has been all on the side of the Democrats from July 21, when Biden stepped down and Harris stepped up, through the end of August—though over the last couple of weeks, it is true, the momentum has begun to shift toward Trump.

So why are forecasters hesitant to greenlight the Harris-Walz ticket? And why indeed do some (let’s flag Nate Silver) insist that Trump maintains a clear edge? There are short-term tactical reasons and long-term strategic reasons. In this essay, I’m going to examine the strategic reasons. And here we’re looking at three, which mostly tilt the playing field to Trump’s advantage: popular-electoral threshold; high-turnout skew; and partisan nonresponse bias. At the end, I’ll come back and discuss some of the tactical reasons.

Popular-Electoral Threshold: Constitutional Design Feature

The popular-electoral threshold arises from the gap between the national popular vote and the electoral college vote. One is what “we the people” do. The other, of course, is what elects the president. And, oh, if you don’t think there should be an electoral college, don’t blame me. Direct your complaints instead to the several dozen statesmen who crowded into a certain sweltering hall in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. They included a procedure for amendment (Article V). Good luck with that.

Ideally, we might think, forecasters should ignore the national popular vote and determine the election winner by forecasting the winning vote in each state. From there, they could simply add up electoral votes. Unfortunately, since state polls are both less frequent and more erratic than national polls, every forecaster has to derive some guidance from how each candidate is doing nationally. And that means asking the following question: Given the likely distribution of votes by state, which now favors the GOP (due to redzone dominance in most low population states), how big a margin does a Democratic candidate need in the national popular vote to gain a 50-50 chance of coming out ahead of the Republican candidate in the electoral college?

Estimates vary. Veteran Democratic advisor James Carville puts it at +3.0%. “Most quants say we have to win by three percent in the popular vote to win in the electoral college,” he says, before then warning his follow Democrats, “So when you see a poll that says we’re two up, well actually we’re one down—if the poll is correct.” Thus, if you read in this morning’s NYT-Siena College national poll that Harris is one down, she’s actually four down.

According to Nate Silver, the threshold is somewhere just under +2.5%. That, in other words, is the national popular margin Harris will need in order to win 50% of Silver’s state-by-state Monte Carlo simulations.

Overall, Silver’s tabulation gives us a good feel for the wide range of possibilities that could be triggered by any given popular vote margin: If we roll the dice again and again, needless to say, who wins any individual election is a crapshoot. Recall that in 2016 Trump narrowly beat Clinton in the electoral college despite losing the popular vote by -2.09%. Clinton would have won if she could have flipped 78K voters in PA, MI, and WI. In 2020, even more remarkably, Trump only narrowly lost to Biden in the electoral college despite losing the popular vote by -4.45%. Trump would have won if he could have flipped 43K voters in GA, AZ, and WI. And Trump wasn’t especially lucky in that election: Only three states in 2020 were decided by a margin of less than one percent—those three—and Biden won all of them by an average margin of a mere 0.4%.

On average, Carville and Silver are no doubt drawing the correct lesson about 2016 and 2020. The Democratic candidate needs a substantial popular vote edge—I’d wager somewhere between 2 and 4 percentage points—to have even odds of winning when the electoral votes are tallied in January.

If anything, Silver’s table (shown above) strikes me as underestimating the threshold.