The share of U.S. children living with married parents has fallen 14 percentage points since the 1980s. This decline is worsening already-significant class divides between college-educated and non-college Americans.

A recent New York Times op-ed by economist Melissa S. Kearney—written in support of her new book The Two-Parent Privilege—sparked a flood of responses debating whether children raised by married parents are really better off than those who aren’t.

In her book, Kearney is unequivocal. She marshals considerable evidence to show that two-parent families are more advantaged than single-parent households. On average, the children in two-parent homes tend to live in households with higher incomes, spend more time with their parents, do better in school, and misbehave less (boys especially)—a resource gap in childhood that carries over into better opportunities and greater educational attainment in adulthood.

Bolstering her argument is a recent piece from Brad Wilcox at the Institute for Family Studies, who writes that, indeed, children raised by married parents experience better social and financial outcomes. In fact, they are comparatively more advantaged today than they were in previous decades.

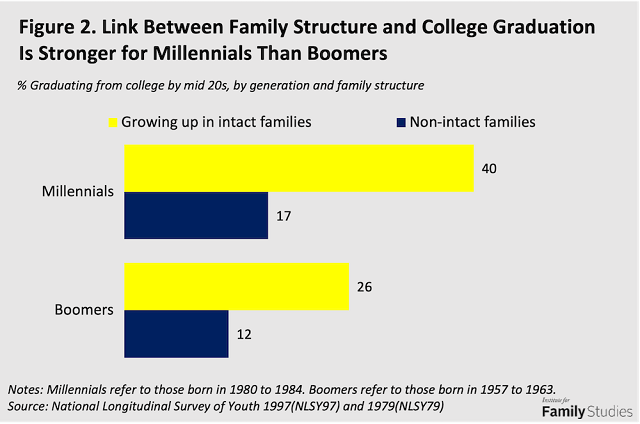

Specifically, Wilcox contends, the relationships between both family structure and children’s college graduation and family structure and children’s economic success have strengthened over time. See the charts below.

Wilcox acknowledges that some of these differences could be attributed to selection since the share of young adults who grew up in married two-parent households has shrunk over time, especially among those who are less educated and have lower incomes. But this larger gap in outcomes persists even after controlling for various socioeconomic characteristics, including race, gender, and parental education.

He hypothesizes that the growing spread is driven by married parents’ increasing level of investment in their kids relative to single parents. This is supported by Kearney’s book: She reports that between the early 1970s and 2006-07, parents in the highest income decile more than doubled their investment spending per child (= spending on things like education, lessons, and games) from $2,832 to $6,573 per year in inflation-adjusted 2008 dollars. Spending among middle-income and low-income parents has also increased, but by much less.

Kearney concludes her book with some suggestions for how U.S. policymakers can promote two-parent families. They include improving the economic position of non-college men to help them be more “marriageable” and promoting a social norm of two-parent families. However, she stops short at suggesting that policymakers promote marriage, noting that the federal government has done so for years but that the program has not meaningfully increased marital stability.

This begs the question: So what does lead to stable married families?

The red-zone model

Policymakers and pundits tend to fall into two camps when answering this question: red zone and blue zone. The red-zone model shepherds young people into marriage typically when they’re young and at the age of first sexual activity. In the heartland, people get married because they put great store in family life and the social norms that underlie marriage. Many are religious.